This post was written by Jeff O’Brien for Simply Residential Property Management Magazine.

People who work in the areas of renting, selling, lending or insuring homes are subject to federal, state and sometimes local fair housing and other anti-discrimination laws. Recently, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (“HUD”) released guidance indicating that landlords who turn down tenants based upon their criminal records may violate the Fair Housing Act. This article focuses on residential landlords’ fair housing responsibilities and tenants’ rights under the Fair Housing Act, particularly in regards to the statute’s prohibitions against discrimination.

Discrimination Claims Under the Fair Housing Act

The Fair Housing Act (the “Act”) is codified at Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq. The HUD regulations implementing the Act are at 24 C.F.R. Parts 100 through 125. The HUD regulations “ordinarily command considerable deference…” Gladstone Realtors v. Village of Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91, 107 (1979). The Act, which applies to both government and private defendants, makes it unlawful to discriminate because of race, color, religion, sex, familial status, national origin

or handicap. 42 U.S.C. § 3604(a), (f). (The words “disability” and “handicap” are used interchangeably.) “Familial status” refers to households with a child or children under 18 or a person who is pregnant or in the process of securing legal custody of a child under 18.

The Act broadly prohibits the refusal to sell, rent, or negotiate for sale or rental, or acts that “otherwise make unavailable or deny” dwellings. It also specifically prohibits making statements indicating preferences (§ 3604(c)) or discriminating in terms, conditions, privileges, services or facilities (§ 3604(b)). It applies to “dwellings,” including vacant land offered for sale or lease for dwellings. The Act has been held to apply to mobile home parks, homeless shelters, and summer homes. See United States v. Columbus Country Club, 915 F.2d 877 (3d Cir. 1990), cert. denied, 501 U.S. 1205 (1991); accord, Hovsons, Inc. v. Township of Brick, 89 F.3d 1096 (3d Cir. 1996) (nursing home). The U.S. Supreme Court has held unanimously that the language of the Act is “broad and inclusive,” implementing a “policy that Congress considered to be of the highest priority,” requiring “a generous construction” of the statute. Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205, 209, 211, 212 (1972).

The Act broadly prohibits the refusal to sell, rent, or negotiate for sale or rental, or acts that “otherwise make unavailable or deny” dwellings. It also specifically prohibits making statements indicating preferences (§ 3604(c)) or discriminating in terms, conditions, privileges, services or facilities (§ 3604(b)). It applies to “dwellings,” including vacant land offered for sale or lease for dwellings. The Act has been held to apply to mobile home parks, homeless shelters, and summer homes. See United States v. Columbus Country Club, 915 F.2d 877 (3d Cir. 1990), cert. denied, 501 U.S. 1205 (1991); accord, Hovsons, Inc. v. Township of Brick, 89 F.3d 1096 (3d Cir. 1996) (nursing home). The U.S. Supreme Court has held unanimously that the language of the Act is “broad and inclusive,” implementing a “policy that Congress considered to be of the highest priority,” requiring “a generous construction” of the statute. Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205, 209, 211, 212 (1972).

It is important to note that intent is not required to establish liability under the Act. Prima facie liability can be established by a showing of disparate effect. The courts of appeals have adopted different standards for determining disparate effect. The Eighth Circuit (which includes the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota) set forth its test to establish a prima facie FHA disparate impact claim in the case of Oti Kaga, Inc. v. South Dakota Housing Dev. Auth, 342 F.3d 871 (8th Cir. 2003). Under the Oti Kaga test, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the objected-to-action results in, or can be predicted to result in, a disparate impact upon a protected class compared to a relevant population as a whole. Oti Kaga, 342 F.3d at 883; see also Charleston Housing Auth. v. U.S. Department of Agriculture, 419 F.3d 729, 740-41 (8th Cir. 2005). Under the second step of the disparate impact burden shifting analysis, the defendant must demonstrate that the proposed action has a “manifest relationship” to the legitimate non-discriminatory policy objectives and “is justifiable on the ground it is necessary to” the attainment of these objectives. Oti Kaga, 342 F.3d at 883; Charleston Housing Auth., 419 F.3d at 741.

The courts recognize two kinds of discriminatory effect: greater adverse impact on one group than another or harm to the community by the perpetuation of segregation. (Arlington Heights II, 558 F.2d at 1290) Greater adverse impact need not mean that more minorities have been affected; if a larger percentage of minorities has been affected, the standard is satisfied.

In some situations there is direct evidence of intentional discrimination. Where there is no direct evidence, a prima facie case may be established by indirect evidence. Some ways of proving intent by indirect evidence are set out by the Supreme Court in Arlington Heights I (Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977)). Another, formulaic way to establish a prima facie case is by showing that: (1) the claimant is a member of a protected class; (2) the claimant applied for and was qualified to rent or buy the property at issue; (3) the claimant was rejected; and (4) the housing opportunity remained available.

After the prima facie case of intentional discrimination has been established, the defendant must produce a legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for its action. If the defendant does so, the burden of production and persuasion shifts to the plaintiff to show that the proffered reason is pretextual.

Remedies

42 U.S.C. § 3613 authorizes a court to award actual and punitive damages, equitable relief, and, to a prevailing party, a reasonable attorney’s fee and costs. In an administrative proceeding, HUD or the state agency may award actual damages, a civil penalty, and injunctive or other equitable relief. 42 U.S.C.§ 3612(g). HUD is authorized to award damages for emotional distress as well as other forms of loss.

The New HUD Guidance

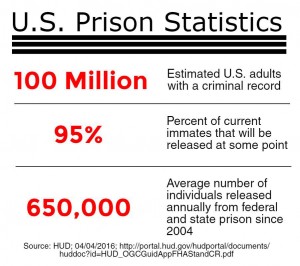

HUD’s basis for its position that landlords may violate the Act by rejecting applicants based upon their criminal records stems from its view that because of widespread racial and ethnic disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system, criminal

history based restrictions on access to housing are likely disproportionately to burden African Americans under the “disparate impact” analysis.

Conclusion

HUD’s recently released guidance should give landlords pause as to their exposure to discrimination claims under the Fair Housing Act. In close cases, consultation with an attorney knowledgeable about the Act is a must.

Jeffrey C. O’Brien is an attorney with the Minneapolis-based law firm of Lommen Abdo, P.A. voice of the “Legal Minute on Minnesota Home Talk, heard Saturdays on 1500 ESPN, and a Minnesota State Bar Association Board Certified Real Property Specialist. He can be reached at (612) 336-9317 or via email at jobrien@lommen.com.

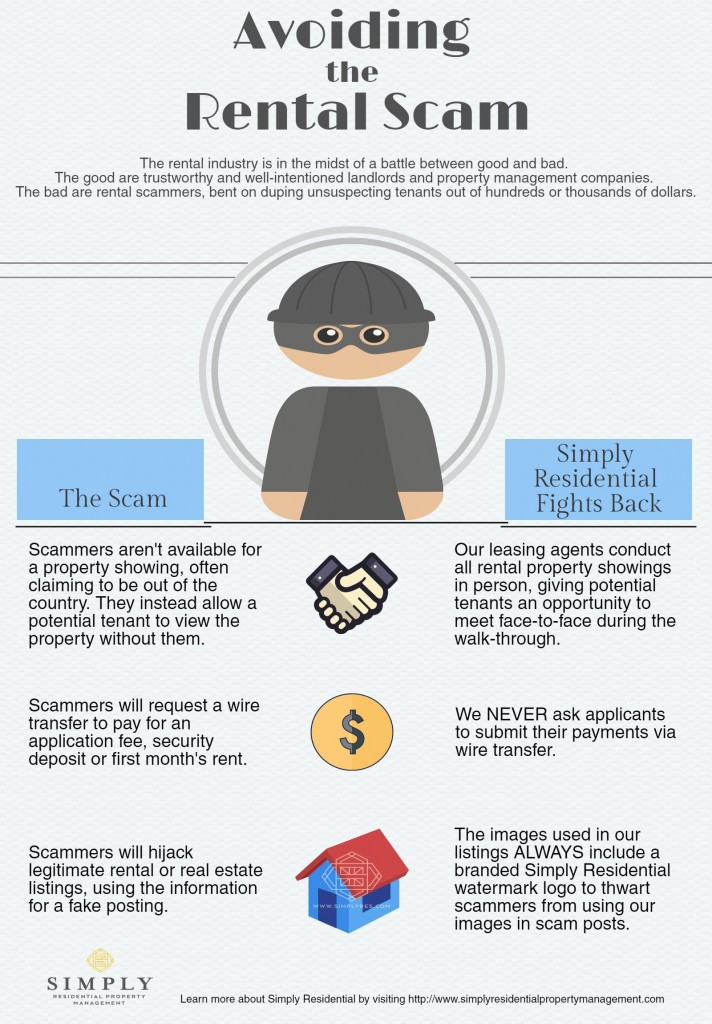

tial tenant realizes, the scam has been completed. The wired money is lost and the scammer is long gone. Rental scams happen every day and it’s unfortunate to hear about the loss and suffering they cause. But there are ways to combat these scams.

tial tenant realizes, the scam has been completed. The wired money is lost and the scammer is long gone. Rental scams happen every day and it’s unfortunate to hear about the loss and suffering they cause. But there are ways to combat these scams.